When you get your diabetes lab results back, you might see two numbers that seem like they should be the same: your A1C and your average glucose. But they’re not always aligned. And that’s not a mistake-it’s a clue. Understanding the difference between these two metrics isn’t just about reading a report. It’s about seeing the full picture of how your blood sugar is behaving over time. One tells you the long-term trend. The other reveals the daily highs and lows. Together, they give you real power to manage your health.

What A1C Actually Measures

A1C, also called HbA1c, is a blood test that shows your average blood sugar over the past 2 to 3 months. It works by measuring how much glucose has stuck to your red blood cells. Since these cells live for about 120 days, the test gives you a stable snapshot of your overall glucose exposure-not just a single day’s spike or drop.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) uses an A1C of 6.5% or higher as the standard diagnostic cutoff for diabetes. For most adults with diabetes, the general target is below 7.0%. But that’s not one-size-fits-all. Older adults, people with frequent low blood sugar, or those with other health conditions might aim for 7.5% or even 8.0%. Personalization matters.

Here’s the key: A1C doesn’t care if your sugar spikes after dinner or crashes at 3 a.m. It only sees the total. That’s why someone could have an A1C of 6.8%-which looks great-but spend 8% of their day below 70 mg/dL. That’s dangerous, and A1C won’t tell you that.

What Average Glucose Really Means

Average glucose is what you see on your glucose meter or continuous glucose monitor (CGM). It’s the mean of all your readings over a period-usually 14 to 90 days. Unlike A1C, it captures the daily rollercoaster: morning highs, post-meal spikes, nighttime dips.

But here’s the twist: when you hear “average glucose” from your doctor, they’re probably talking about estimated average glucose (eAG). That’s not a direct measurement. It’s a math conversion from your A1C percentage into the units you already know: mg/dL.

The formula is simple: eAG (mg/dL) = 28.7 × A1C − 46.7. So if your A1C is 7.0%, your eAG is 154 mg/dL. If it’s 8.2%, your eAG is around 190 mg/dL. The ADA has a handy chart:

- A1C 6.0% = 126 mg/dL

- A1C 7.0% = 154 mg/dL

- A1C 8.0% = 183 mg/dL

- A1C 9.0% = 212 mg/dL

- A1C 10.0% = 240 mg/dL

This conversion helps bridge the gap between lab results and your daily life. If you’re used to checking your meter and seeing 140 mg/dL, seeing “eAG 154” makes it easier to connect the dots.

Enter GMI: The New Player

In 2019, a new term entered the scene: Glucose Management Indicator (GMI). Unlike eAG, which is calculated from A1C, GMI is calculated directly from your CGM data. It uses the same formula as eAG but is based on real-time, continuous readings-often over 14 days or more.

Why does this matter? Because GMI reflects what your glucose monitor actually saw, not what your blood test estimated. In one study of over 5,700 people, GMI and A1C differed by more than 0.5% in nearly 1 in 4 patients. That’s not small. It means your CGM might be showing you a different story than your lab.

For example: Your CGM shows an average of 162 mg/dL. That gives you a GMI of 7.3%. But your A1C comes back at 6.8%. That mismatch isn’t a lab error. It’s a signal. Maybe you’re having frequent lows that your body is compensating for, or your red blood cells are turning over faster due to anemia or kidney disease. GMI helps catch those hidden patterns.

Why the Numbers Don’t Always Match

It’s not uncommon to have an A1C that seems “too low” compared to your daily glucose readings-or vice versa. Here’s why:

- Red blood cell lifespan varies. If you have anemia, kidney disease, or recent blood loss, your cells don’t live the full 120 days. That can make your A1C appear lower than your actual average glucose.

- Glucose spikes matter more than you think. A1C averages everything. But if you’re spending hours above 200 mg/dL after meals and then crashing to 60 mg/dL overnight, your A1C might still look “good.” Your CGM tells you the truth: you’re swinging wildly.

- Testing timing affects results. Fasting blood sugar can vary by 5-10% just from stress, sleep, or illness. A1C doesn’t care about any of that. It’s stable.

- CGM accuracy isn’t perfect. Even the best sensors have a margin of error. GMI is only as good as the data you feed it.

One user on a diabetes forum shared: “My A1C was 6.8%, but my CGM showed I was below 70 mg/dL for 8% of the day. My doctor didn’t even mention the lows because my A1C was ‘in range.’” That’s the danger of relying on one number alone.

What Experts Really Think

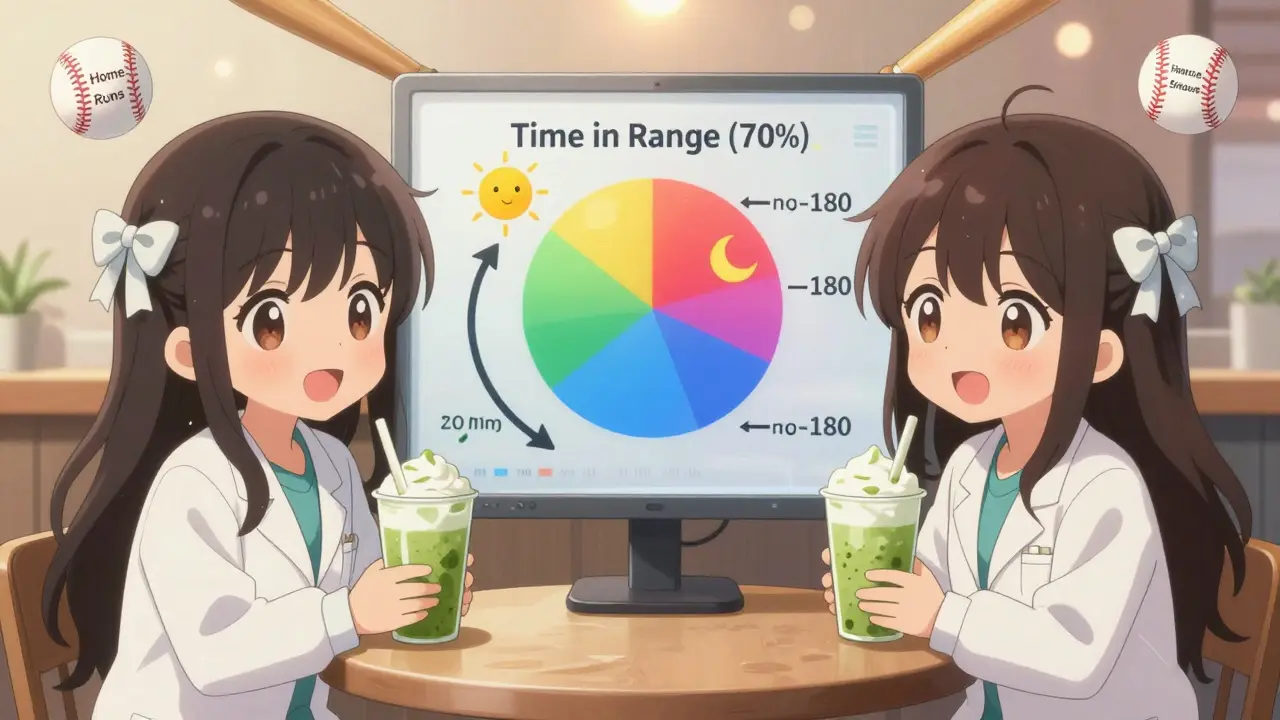

Dr. Richard Bergenstal, a leading diabetes specialist, says: “Time in Range (TIR) should be your primary goal. A1C is the summary report.” TIR means how many hours a day your glucose stays between 70 and 180 mg/dL. The ADA recommends aiming for at least 70% of the day in that range.

That’s a game-changer. Instead of just asking “Is my A1C under 7%?” you start asking: “How often am I going too high? Too low? For how long?”

Dr. John Pickup from Imperial College London warns: “A1C can be misleading in conditions that affect red blood cells.” That includes sickle cell disease, iron deficiency, pregnancy, or even heavy alcohol use. In those cases, CGM data and GMI are more reliable.

The ADA’s own 2024 guidelines now emphasize “glycemic individualization.” Your target isn’t just a number on a chart. It’s shaped by your age, risk of lows, other health conditions, and even your lifestyle.

How to Use Both Metrics Together

Don’t pick one over the other. Use them as teammates.

Here’s how:

- Check your A1C every 3-6 months. If your control is stable, twice a year is fine. If you’re adjusting meds or lifestyle, every 3 months gives you better feedback.

- Use CGM data weekly. Download your 14-day report. Look at your GMI. Compare it to your A1C. If they’re more than 0.5% apart, talk to your provider.

- Track Time in Range. Aim for 70% or more of your day between 70-180 mg/dL. Keep time below 70 mg/dL under 4%. Time above 180 mg/dL should be under 25%.

- Don’t ignore lows. If your A1C looks good but you’re having frequent hypoglycemia, your treatment plan might be too aggressive. Your CGM is your early warning system.

Think of A1C like a baseball player’s season batting average. It tells you how well they performed overall. But if you only look at the average, you miss the home runs, the strikeouts, and the bunts that saved the game. Your daily glucose readings are those at-bats.

What Your Targets Should Be

There’s no universal target. But here are common guidelines based on current standards:

- Most adults with diabetes: A1C < 7.0%, eAG < 154 mg/dL, TIR ≥70%

- Younger, healthy people with type 1: A1C < 6.5%, eAG < 140 mg/dL, TIR ≥75%

- Older adults or those with multiple health issues: A1C < 7.5-8.0%, eAG < 170-183 mg/dL, TIR ≥60%

- People with frequent lows: A1C target may be higher (e.g., 7.5-8.0%) to reduce hypoglycemia risk

Remember: Your goal isn’t to hit a number. It’s to live without dangerous highs and lows.

What’s Next in Diabetes Monitoring

The field is shifting fast. By 2027, experts predict Time in Range will replace A1C as the primary target in clinical trials. Why? Because it shows real-time behavior, not just an average.

Research from the T1D Exchange registry shows that using both A1C and GMI together reduces treatment errors by 23%. That’s huge. It means fewer missed lows, fewer unnecessary medication changes, and better outcomes.

Even the FDA is catching on. In 2022, it approved TIR as a primary endpoint in new drug trials. That’s a sign this isn’t just a trend-it’s the future.

For now, you don’t need to wait for the future. Start using your CGM data. Ask for your GMI. Compare it to your A1C. Talk to your care team about your Time in Range. You’re not just managing diabetes-you’re learning how your body responds to food, stress, sleep, and activity. And that knowledge? That’s the real treatment.

Siobhan K.

December 21, 2025 AT 01:34A1C is just the government’s way of making us feel good about numbers that don’t reflect real life. I had a 6.8% A1C while spending 12% of my day under 60 mg/dL. My doctor said ‘you’re doing great’ - until I showed him my CGM graphs. Then he went quiet for ten minutes. That’s when I knew I needed a new doctor.

Brian Furnell

December 22, 2025 AT 05:03It's critical to recognize that GMI, derived from continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data, offers a far more granular, temporally-resolved metric than A1C - which is, by design, a weighted average of erythrocyte glycation over a 120-day lifespan. The discrepancy between A1C and GMI isn't noise - it's a physiological signal, often indicative of glycemic variability, erythropoietic turnover, or hemoglobinopathies. In clinical practice, we now treat these metrics as complementary, not interchangeable - and I'd argue that TIR (Time in Range) is the true north for therapeutic decision-making.

Cara C

December 22, 2025 AT 22:31I used to obsess over A1C like it was a report card. Then I got a CGM and realized I was crashing every night after dinner. My A1C was 6.9% - ‘perfect’ - but I was waking up terrified. Now I look at my Time in Range. That’s what matters. I sleep better. I live better.

Stacey Smith

December 23, 2025 AT 16:37Why do we even use A1C? It’s outdated. The FDA should ban it. CGM data is real. GMI is real. A1C is a relic from the 1980s. Stop letting labs lie to you.

Teya Derksen Friesen

December 24, 2025 AT 10:24It is imperative to acknowledge the nuanced interplay between laboratory-derived metrics and real-time physiological data in the context of diabetes management. The Glucose Management Indicator, being derived directly from continuous glucose monitoring systems, provides a more accurate representation of glycemic exposure than the historically entrenched Hemoglobin A1c, which is subject to confounding variables such as erythrocyte turnover, hemoglobin variants, and iron deficiency states. Consequently, the integration of GMI and Time in Range as primary outcome measures represents a paradigm shift toward personalized, data-driven care.

Jason Silva

December 25, 2025 AT 23:39They don't want you to know this... but A1C is manipulated by Big Pharma to keep you on insulin. Your CGM shows the truth - they don't want you seeing how often you're crashing because then you'd ask why you're getting 3 shots a day. GMI? That's the real data. A1C? A distraction. 🕵️♂️💉

mukesh matav

December 26, 2025 AT 13:00In my country, we don’t have CGMs for everyone. A1C is still the only thing we can rely on. I understand the value of GMI, but not everyone can afford it. Let’s not forget the global reality - good care shouldn’t depend on how rich you are.

Theo Newbold

December 28, 2025 AT 00:05Let’s be brutally honest: if your A1C and GMI differ by more than 0.5%, your doctor is either incompetent or lazy. 23% reduction in treatment errors? That’s not a study - that’s a wake-up call to every endocrinologist still using 1995 guidelines. Your A1C is a lie. Your CGM is the truth. Stop wasting time.